The Covid-19 Pandemic Worsened Mental Health:

How We Can Better Address Mental Health Needs in the Future

By Zoe Verma, Associate with TalentNomics Inc.

Like everyone, the Covid-19 global pandemic changed my life in countless ways. As a high school student, the first thing I think of is school. Overnight, my normally rigorous, busy schedule changed to waking up fifteen minutes before class and walking over to my desk to get on Zoom. And although I never thought I would say this, I really missed being at school. Along with so much we found enjoyable, many of us also saw the disappearance of our support systems. The increased focus on physical health during the pandemic, while understandable, took the spotlight away from mental health. To me, it seemed that the emphasis on mental health was just starting to grow before the pandemic, but with the onset of the deadly virus, physical symptoms became the main focus. It felt like we had forgotten about the importance of mental health during the crisis. At school, students and teachers had contact with their peers, schools’ mental health professionals, and others to talk to whenever there was a pressing worry. But during Covid, Zoom and FaceTime completely changed the personal connection that was achieved in face-to-face interactions, a change that affected me in many ways. And while this change has been hard for every teacher, student, and parent, I have faith that as a community we will learn from the pandemic to see the equal importance of mental health, and we will learn ways to check in with each other.

During the pandemic, data collected showed that mental health in the U.S. declined. Even as someone who hadn’t previously faced mental health issues, I experienced a downturn in my mental health and overall mood. And while these declines and swings are not abnormal, two events that happened in the past year were especially hard to cope with because of the isolation I was feeling.

In March 2020, my beloved grandmother passed away. I loved her and was severely affected by her death. She was a truly incredible woman: a Pulitzer Prize nominee (though she would not want me writing that!), the daughter of Armenian Genocide survivors, an Armenian translator at the United Nations, and a loving mother and grandmother. Her death was especially difficult because it coincided with the very beginning of the pandemic. My father and I flew to her funeral on March 5, which was exactly eight days before my school was closed. In these early days of the pandemic, we did not understand the importance of masks. Before my dad and I left, my mom, who drove down earlier with my younger siblings, told us to bring masks “just in case.” She highly recommended that we wear them, but my dad and I were reluctant. When we got to the airport, only a few people were wearing masks, and I remember staring at them, thinking how strange they looked. Once on the plane, I wore my mask for the short flight, but I felt strange doing so. I still remember wondering what was happening to the world.

After her funeral, I returned to school, ready to be around my friends to help me process her death. Little did I know, I would have only five days with them before being confined to my house. And in my house, I was alone with my thoughts. I had no friends, no interactions, no greetings in the hallway to distract me from what I was feeling. I knew how much easier it would have been to be at school; in fact, the days I spent at school after her death had helped me process my grief. I talked to teachers and friends about her, and it truly did make me feel better. I remember sharing that I was nervous because it was my first funeral, and I didn’t want to see any of my family members upset. My friends reassured me that everything was going to be okay, and I believed them. They helped me, and looking back on it, I took such simple interactions for granted. And then I went through this whole process all over again just six months later. Instead of being able to easily talk to my friends in the hallway, I again found myself alone in my room with my thoughts and immense sadness.

In September 2020 my Uncle Britt passed away very suddenly. He was a second father to me. He taught me how to drive, and every time we visited him in South Carolina he would take me out to practice, unfazed by my extremely subpar skills. I have so many funny memories of him and the things we used to do together, and I miss him dearly every day. The first month after his death was one of the hardest months I have ever experienced. I felt hopeless and alone knowing that I couldn’t go to school to distract myself and seek comfort. I was, yet again, alone in my room with my thoughts and my incredibly overwhelming sadness. I felt constantly sad with no escape. Now that I am on the other side of that experience, I am proud to say that I made it through. But many others who faced challenges along with mental health conditions, whether diagnosed or undiagnosed, feel they have not yet made it to the other side, and many may feel like they never will.

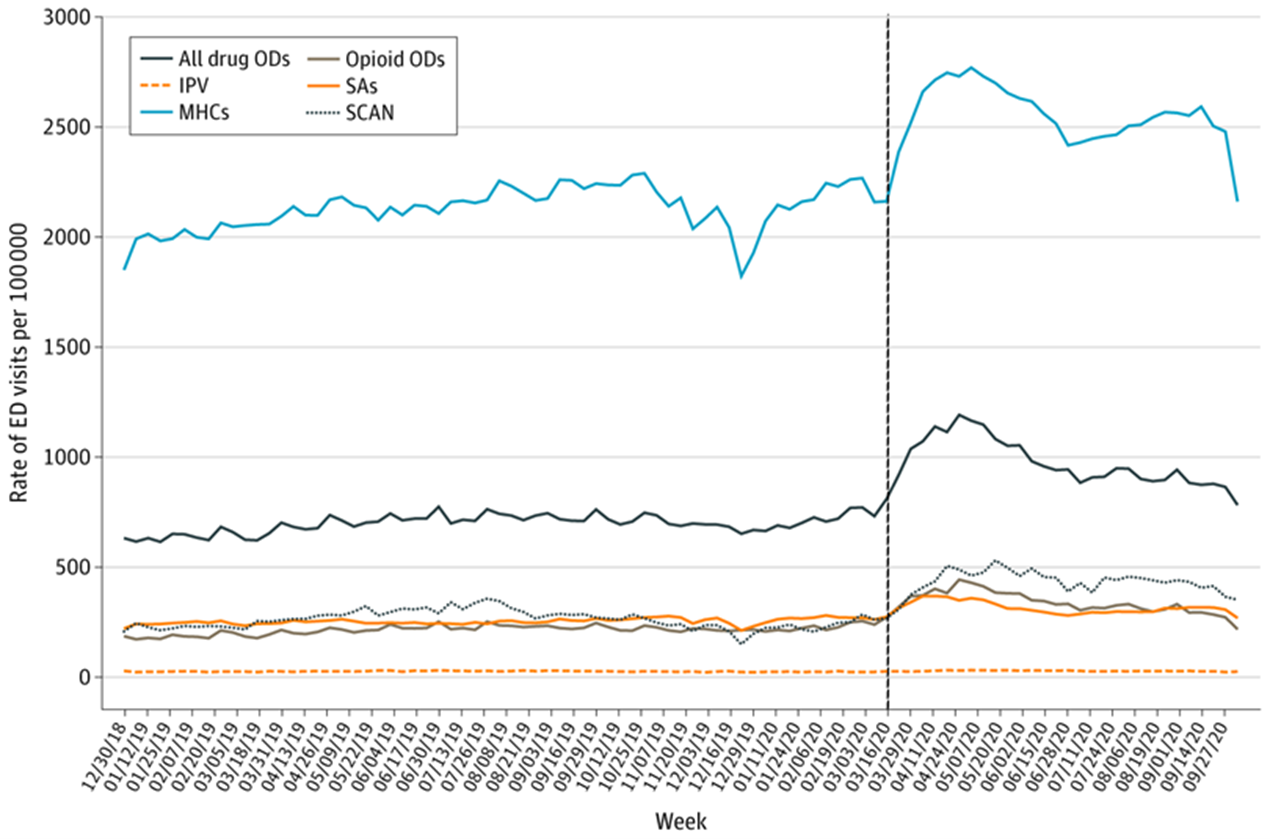

Increased ER Visits

Studies show that mental health in the U.S. declined during the pandemic, leading to a record increase in mental-health-related emergency room (ER) visits.  A study conducted of 190 million ER visits for “mental health conditions, suicide attempts, all drug and opioid overdoses, intimate partner violence, and child abuse and neglect,” showed that visit rates were much higher in mid-March through October 2020, during the COVID pandemic, compared with the same period in 2019.(Read More) ER visits due to other mental health conditions (MHCs), defined as any condition that could be worsened by the pandemic, “such as stress, anxiety, symptoms consistent with acute stress disorder or posttraumatic stress disorder, and panic” also increased significantly, with 41,075 MHC-related visits in 2020, versus 39,366 visits in 2019. In addition to this rise of over 1,700, the rate of MHC-related visits also increased drastically: in 2019, there were 2110.2 visits per 100,000 visits, and in 2020, this had risen to 2436.7 visits per 100,000 visits.

A study conducted of 190 million ER visits for “mental health conditions, suicide attempts, all drug and opioid overdoses, intimate partner violence, and child abuse and neglect,” showed that visit rates were much higher in mid-March through October 2020, during the COVID pandemic, compared with the same period in 2019.(Read More) ER visits due to other mental health conditions (MHCs), defined as any condition that could be worsened by the pandemic, “such as stress, anxiety, symptoms consistent with acute stress disorder or posttraumatic stress disorder, and panic” also increased significantly, with 41,075 MHC-related visits in 2020, versus 39,366 visits in 2019. In addition to this rise of over 1,700, the rate of MHC-related visits also increased drastically: in 2019, there were 2110.2 visits per 100,000 visits, and in 2020, this had risen to 2436.7 visits per 100,000 visits.

Substance Abuse

After March 2020, drug and alcohol abuse grew more serious and dangerous, likely in part due to the isolation caused by the pandemic. In the first 41 weeks of 2020, there were 2,068 more ER visits due to overdoses than there were in the same period in 2019. In April of 2020, the Addiction Policy Forum surveyed 1,079 people with substance use disorders across the country on how the pandemic had affected their disorders, and the results were striking.

20% of the respondents reported that their own or a family member’s substance use had “increased since the start of the pandemic.” ( Read More ) One of the most common concerns of the surveyed individuals was the “lack of access to in-person 12-step or support group meetings.” People cited changes to services they had relied on, including the closure of in-person recovery centers. They also cited finding themselves without the “ability to socialize/connect or get peer support.” This lack of interaction and connection clearly affected many people in need and exacerbated an already grave problem. In fact, when Millennium Health analyzed 500,000 urine drug tests nationwide, they found “steep increases following mid-March [2020] for cocaine (up 10%), heroin (up 13%), methamphetamine (up 20%), and non-prescribed fentanyl (up 32%).” These increases in drug use occurred directly after COVID-19 began. It is clear that isolation and support system failures had affected these individuals, prompting many to turn to or increase their use of drugs.

Suicide Attempts

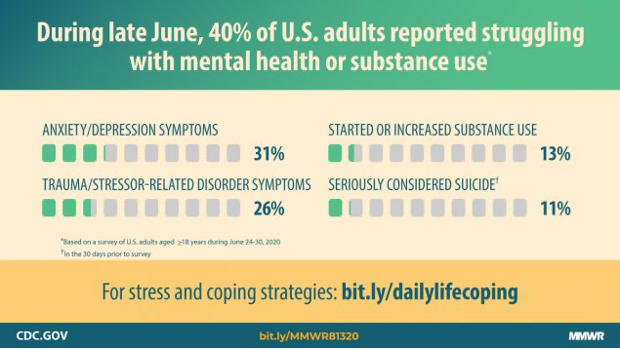

Suicide attempts also increased after the start of the pandemic. Studies that modeled the effect of the pandemic on suicide rates predicted increases of up to 145%.( Read More )  There were 416 more ER visits related to suicide attempts in the first 41 weeks of 2020 compared to the same period in 2019 ( Read More ). In June 2020, just three months into the pandemic in the U.S., surveys were conducted to determine the pandemic’s impact on mental health conditions. They showed that 40% of U.S. adults reported struggling with mental health or substance use at the time of the survey. And of the 5,470 adult respondents to the survey, 10.7% of them reported that they had considered suicide in the previous 30 days.( Read More ) This increase in suicidal ideation could be attributed to the “effects of public health measures to combat COVID-19,” such as “physical distancing, school closures, interventions to address loss of income, [and] interventions to tackle domestic violence.”( Read More ) In addition, “changed and new approaches to clinical management”( Read More ) of known suicidal patients could also contribute to the rise in suicidal thoughts.

There were 416 more ER visits related to suicide attempts in the first 41 weeks of 2020 compared to the same period in 2019 ( Read More ). In June 2020, just three months into the pandemic in the U.S., surveys were conducted to determine the pandemic’s impact on mental health conditions. They showed that 40% of U.S. adults reported struggling with mental health or substance use at the time of the survey. And of the 5,470 adult respondents to the survey, 10.7% of them reported that they had considered suicide in the previous 30 days.( Read More ) This increase in suicidal ideation could be attributed to the “effects of public health measures to combat COVID-19,” such as “physical distancing, school closures, interventions to address loss of income, [and] interventions to tackle domestic violence.”( Read More ) In addition, “changed and new approaches to clinical management”( Read More ) of known suicidal patients could also contribute to the rise in suicidal thoughts.

Clearly, a common issue among those in need is isolation and forced physical separation from friends, family, and doctors. The need for interaction or connection tends to be overlooked as a desire; it is rarely considered a need. It appears from the data, though, that many people truly need social interaction and a strong support system to help them survive, and we as a community have a responsibility to help provide such a support system for those who require it.

The isolation and the stress of the pandemic, coupled with the loss of loved ones and livelihoods, intensified mental health issues in the US. Therefore, as we move out of the pandemic and in the post-pandemic era, we must recognize the importance of mental health and the urgency of helping our community members in need.

Mental health is also strongly correlated with physical health. According to the CDC, “mental illness, especially depression, increases the risk for many types of physical health problems, particularly long-lasting conditions like stroke, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease.” ( Read More ) The UK-based Mental Health Foundation found that “schizophrenia is associated with a tripled risk of dying from respiratory disease and a doubled risk of dying from a form of heart disease. Depression has been linked to a 50 percent increase in a person’s risk of dying from cancer and a 67 percent increase from heart disease.”( Read More ) Mental health conditions can lead to life-threatening diseases, and possibly a shortened life span. This is because “mental health is more than the presence or absence of a mental illness. It is a crossroad between emotional, psychological, and physical well-being.” ( Read More ) Our mental health defines the way we live our lives, which is why it should be prioritized by our policymakers and within our communities.

Looking Forward

In the future, there are many ways that we as a community can prioritize mental health issues. For us students, this can best be done at school, as teachers and administrators are often the first to notice any sort of issue. Of course, each person has their own set of symptoms when it comes to their conditions, but there are a few general things adults in schools should look for. For example, if a teacher notices a student is sad or withdrawn for more than two weeks, they should check in with the student, and open up communication. Any out-of-the-ordinary or out-of-control behavior should also be a warning sign, including fighting, changing eating patterns, and abnormal mood swings. Recognizing such warning signs is important, and having a plan in place to address mental health conditions is crucial. It would also be useful for schools to provide access to mental health professionals who can help students and teachers with mental health concerns. It also would be useful to allocate or allow days off from school to provide mental health breaks.

In the future, there are many ways that we as a community can prioritize mental health issues. For us students, this can best be done at school, as teachers and administrators are often the first to notice any sort of issue. Of course, each person has their own set of symptoms when it comes to their conditions, but there are a few general things adults in schools should look for. For example, if a teacher notices a student is sad or withdrawn for more than two weeks, they should check in with the student, and open up communication. Any out-of-the-ordinary or out-of-control behavior should also be a warning sign, including fighting, changing eating patterns, and abnormal mood swings. Recognizing such warning signs is important, and having a plan in place to address mental health conditions is crucial. It would also be useful for schools to provide access to mental health professionals who can help students and teachers with mental health concerns. It also would be useful to allocate or allow days off from school to provide mental health breaks.

Finally, community members can take the lead by discussing the importance and significance of mental health. If mental health is openly discussed it will help to lessen the stigma, allowing people to feel they have judgment-free zones to find available resources.

In the multi-cultural US, it is also important to consider different cultural views on mental health. As someone with Indian, Armenian, and American roots, I have witnessed different types of stigmas around mental health. For example, I have found that Indians tend to completely ignore the importance of mental health, hiding mental health conditions away from view. This is a very unhealthy attitude, as it can exacerbate the severity of mental health conditions. This attitude can be seen across various cultures. To help break the harmful stigma around mental health, we must all commit to talking openly and freely about mental health conditions, while at the same time educating ourselves on this central part of our lives. If we all commit to working together to break the stigma, I believe many people will benefit and begin to experience better mental health in the future.

Leave a Reply