Shrinking the gender promotion gap:

Where there is a will, there is a way 1

Our mission at TalentNomics is to achieve gender balance in leadership positions. While there has been much progress in educational attainment of women, there is still a large gender gap in career outcomes between men and women in many professions.

1By Luc Laeven, a member of the board of TalenNomics Inc. The views expressed are my own and do not reflect those of the European Central Bank.

Why the gap?

Several explanations may account for the lack of women in leadership positions. One possibility is that the pool of potential candidates is male dominated. An alternative explanation is that women are less likely to seek leadership positions because of family considerations or different job preferences. The imbalance may also be reinforced by self-fulfilling expectations, whereby the low representation of women at the top of the field discourages others to pursue careers in these fields. Finally, there may be gender-based discrimination in promotion decisions and the selection among potential candidates.

Several explanations may account for the lack of women in leadership positions. One possibility is that the pool of potential candidates is male dominated. An alternative explanation is that women are less likely to seek leadership positions because of family considerations or different job preferences. The imbalance may also be reinforced by self-fulfilling expectations, whereby the low representation of women at the top of the field discourages others to pursue careers in these fields. Finally, there may be gender-based discrimination in promotion decisions and the selection among potential candidates.

Which of these explanations is more relevant? And can corporate diversity policies foster a change in outcomes?

To answer these questions, I launched a major research initiative at my current employer, the European Central Bank (ECB), to analyze the career progression of men and women. The ECB is the central bank of the euro area, and it employs many economists among its professional staff. As in other major central banks its cadre of professional staff is dominated by men and the gender imbalance increases at more senior levels. This “leaky pipeline” of women is a general feature of the economics profession. According to data from the Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession, women account for 28.8 percent of PhD graduates but only a mere 13.9 percent of full professors in economics in the United States. The picture is similar in the rest of the world. The underrepresentation of women is perhaps nowhere as visible as at central banks, the recent appointment of Christine Lagarde as President of the ECB being a welcome but rare exception to what is very much a male-dominated field.

Female Professionals at the ECB

The research, conducted jointly with Laura Hospido and Ana Lamo, analyses the career progression of men and women at the ECB, using confidential anonymized personnel data from its professional staff during the period 2003-2017. Our analysis focuses on expert staff across four different salary bands representing different levels of seniority (expert, senior expert, principal expert and advisor) in those departments of the ECB that employ economists. With this selected group, we focus on a broadly homogeneous pool of workers in terms of educational attainment and work experience, ensuring comparability across individuals. Moving up to a higher salary band requires a promotion.

We find that a wage gap emerges between men and women within a few years of hiring, despite broadly similar entry conditions in terms of salary levels and other observables. One important driver of this wage differential is the lack of promotion of women. We also find that the wage gap shrinks after the ECB issues a public statement in 2010 supporting gender diversity and takes several measures to support gender balance. These concrete measures included expanded mentorship programmes, enhanced childcare benefits and more flexible work arrangements, and the introduction of gender quota. Following this change, the promotion gap disappears.

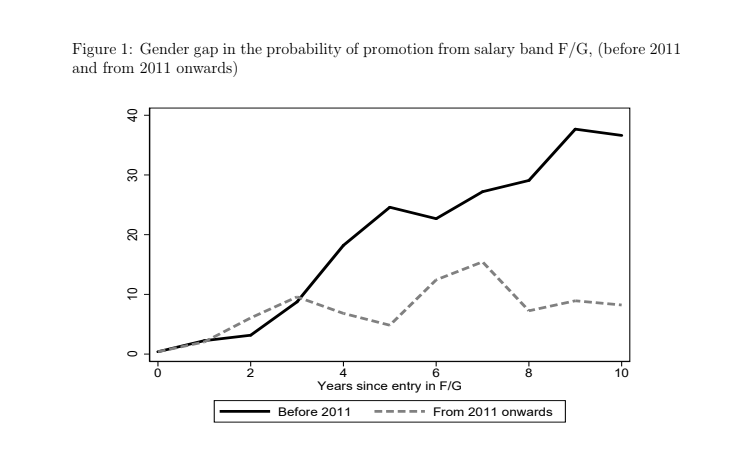

Figure 1 shows in more detail that this change in diversity policies in 2010 had material effects on gender differences in promotion outcomes. The figure focuses on promotions from salary band F/G, which is the entry level salary band for professional economists at the ECB. The gender gap in promotions is defined as the difference in the promotion rates of men and women. The promotion gap narrowed from 2011 onwards, following the policy change. While prior to 2011, the gender promotion gap stood at over 36% after ten years since entry, this gap decreased to about 8% on average after 2011, or a decline of about 80 percent.

Source: Hospido, L., Laeven, L. and Lamo, A. (2019), “The gender promotion gap: evidence from central banking”, Working Paper Series, 2265, European Central Bank. Forthcoming in the Review of Economics and Statistics.

Note: The chart illustrates the gender gap related to the average annual probability of promotion (moving from Expert level to Principal expert or Adviser level) since entry at Expert level (Band F/G) before 2011 and from 2011 onwards.

Using 2012-2017 data on promotion applications and decisions, we explore the promotion process following the new diversity strategy in depth, and confirm that during this most recent period women are as likely to be promoted as men. This results from a lower probability of women to apply for promotion, combined with a higher probability of women to be selected conditional on having applied. We coin this reluctance to apply for promotions the gender applications gap. Following promotion, women perform better in terms of salary progression, suggesting that the higher probability to be selected is based on merit, not positive discrimination. We do not find evidence that the composition of the selection committee, including the fraction of women on the panel, alters these results. Taken together, these results show that corporate diversity policies can effectively reduce gender bias in promotions.

Conclusions

Understanding the main drivers of the observed gender promotion gap is critically important to improve our understanding of how we can close the gender gap and ensure that women are adequately represented. The ECB experience shows that a well-designed gender strategy that includes concrete measures can improve the gender balance and foster a more inclusive environment. Our research findings suggest that a key measure of success is an environment in which women seek promotions at the same rate as men. This requires removing any institutional barriers that prevent women to seek promotions while steering outcomes toward a better equilibrium where there is no place for selection biases and self-fulfilling expectations. Much of this needed change can come from within, and companies should embrace and rise to this challenge.

Leave a Reply